The piece of information from the 1851 census – that John McFall was a seaman in his younger days – gives direction to further investigation, resulting in a reference to John in a maritime journal. The free first page of the online version of an article by M.K. Stammers in the ‘Mariner’s Mirror’, volume 2 (1976) indicates that a deposit had recently been given by the family of John McFall to the Maritime Museum in Liverpool. The deposit included letters, a log and personal artefacts. From these, details about John and his voyages are revealed. The writer notes that John was born in 1825 and at the age of fifteen apprenticed to the East India Merchants, Taylor & Co.

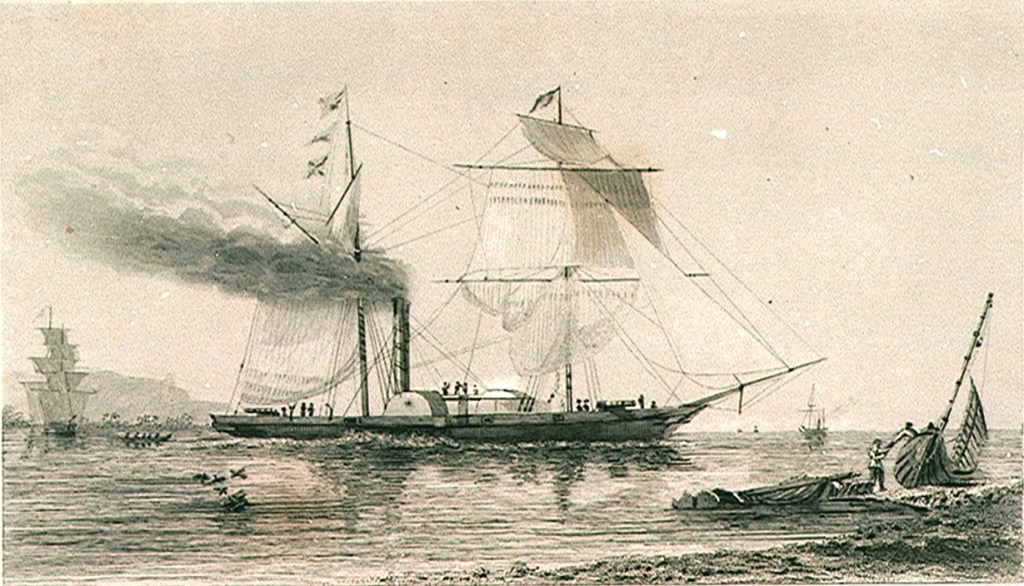

The cache indicates that John sailed in the first oceangoing iron warship, Nemesis, which was built in Laird’s Birkenhead shipyard in 1839 and used in the Opium Wars. The ship proved to be an effective weapon in the areas she was deployed and was known by the Chinese as “the devil ship”. In his log, John speaks of the dangerous adventures he had in China and India.

Stammers’ examination of the documents shows that in 1848 John also sailed on Cunard’s first transatlantic liner RMS Britannia. She was later to be bought by the German Empire Navy and be renamed SS Barbarossa.

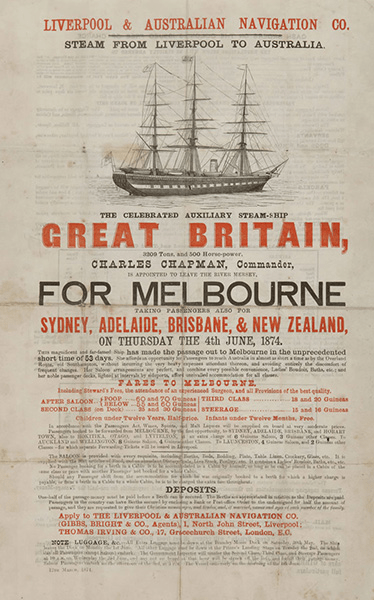

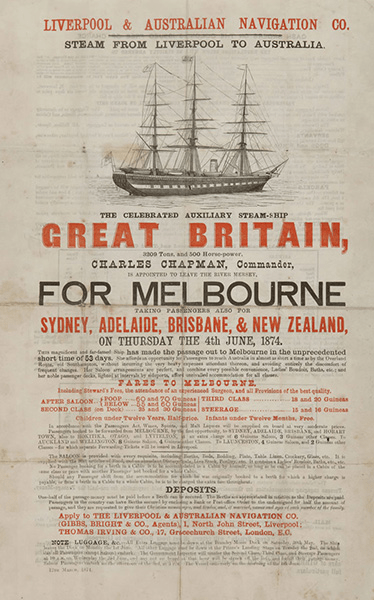

In 1852 he served as boatswain on Brunel’s recently refitted SS Great Britain – “the greatest experiment since the Creation” – with over 600 passengers bound for Melbourne and the gold rush. His letters apparently give an impression of the feverish atmosphere of those times.

The ship is now exhibited in Bristol and the website for the museum indicates that John was on a voyage to New York prior to the Australian adventure. The advertisement for the Melbourne voyage is also displayed there.

The collection that the family donated in the mid-1970s also indicates that John was a “dedicated seeker of knowledge”, his journal showing that while on board he worked on navigational problems. He was also an accomplished linguist and late in life became a distinguished Hebrew scholar. During our quarantine, there has been great encouragement to take up new hobbies and learn new things. We are offered MOOCs, on-line guidance videos and the chance for shared experience through Zoom. We might wonder how John managed to fashion his own diverse education.

Returning to the census records, we that in 1841 there is a John McFall living in Crump Street, off Greenland Street. He is fifteen (which fits) and living with the Powell family. His profession is given as ‘blacksmith’. If him, would this be the first stage of the apprenticeship? There is little else at this location now, other than, incidentally, an iron scrap company.

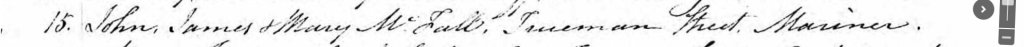

Eventually a record is found that give an indication of when he was born. His baptism took place in Saint Peter’s, Everton on 15th December 1824. His parents, Mary and James, are located in Trueman Street, just around the corner from the Ship and Mitre, Dale Street.

And perhaps not surprisingly, his father is described as a mariner.

Our plaque on Bankfield Street has gradually given up its secrets. We have discovered the verses of scripture that John chose for the home that he presumably built. We have learnt a little of his family and work, and caught glimpses of that earlier adventurous life on the sea. John was a skilled and respected seaman and builder. With Catherine he created a family who would in their own turn would leave their mark on this locality. And he had an immense passion for learning. The sandstone plaque, easily missed, opens worlds beyond the confines of our suburban lockdown.

Postscript

A curious footnote to the story of the plaque concerns John and Catherine’s son, John Ewart Whitley MacFall. Unlike his brother who went on to take over the building business, John trained to be a doctor. (His middle names are probably derived from the Lord Mayor of Liverpool a couple of years before John junior was born.) By 1900 he had set up a practice on Green Lane and was living in 340 West Derby Road – the last house on the terrace by the Tuebrook roundabout. He served in the Royal Army Medical Corps during the First World War and trained further to become Professor of Forensics. MacFall became the much-maligned expert witness in the Julia Wallace ‘telephone murder’ case of 1931.